Política de las formas

Chilean artist Voluspa Jarpa’s work has enquired into the capacity to reverse the prevalent conditions of censorship in our history’s most compromising documents. Following the declassification carried out in the United States in relation to the 1973 coup d’état against Chilean president Salvador Allende, the artist initiates a very sophisticated debate on archival legibility.

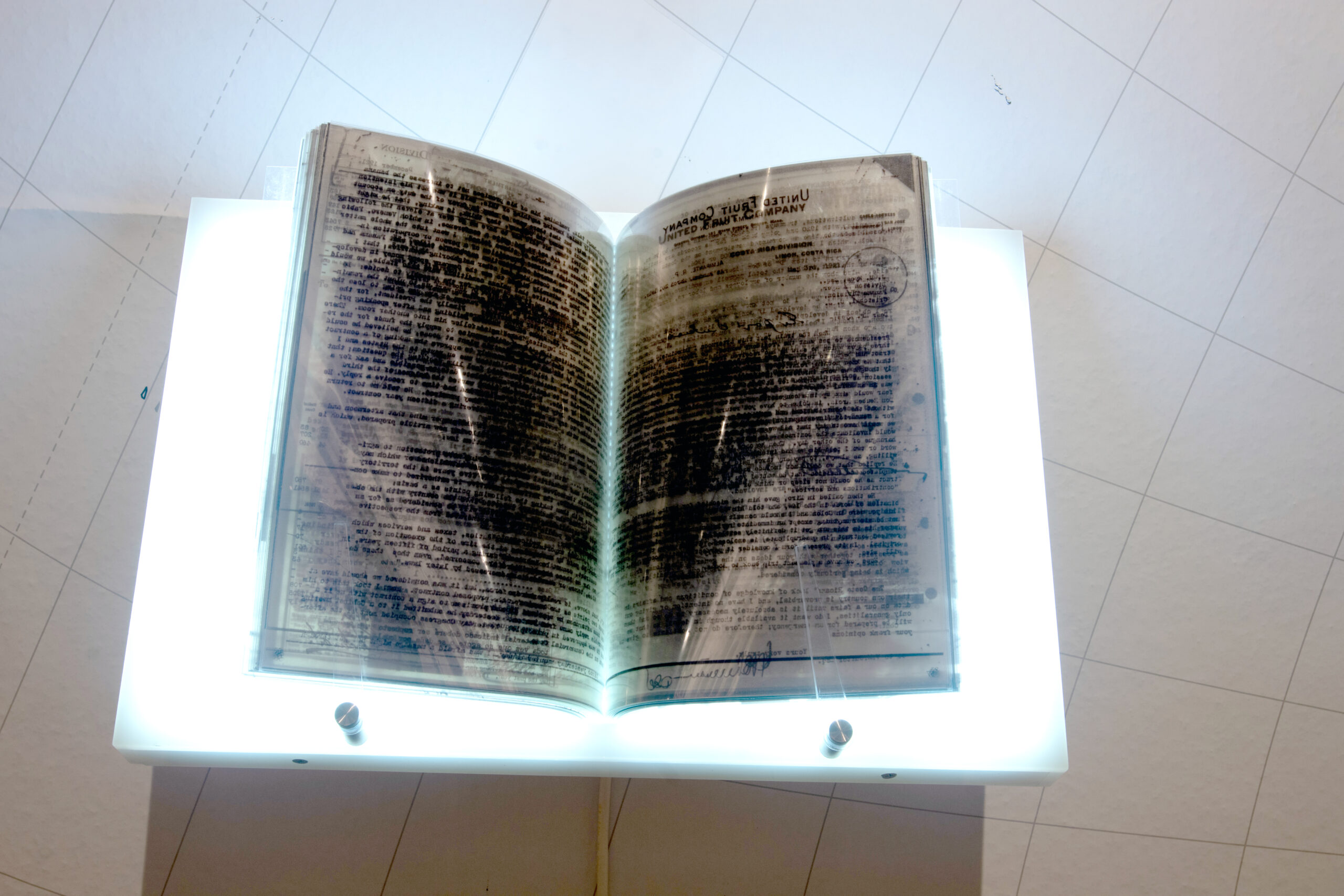

Jarpa acknowledges the relevance of the medium, its compositional condition and, therefore, the materiality of the political document. However, the artist is interested in the negative portion, in that which is apparently illegible or empty, in order to emphasise that the archive is above all a material problem. A device in which the medium is not only relevant, useful or conveyor, but merely definitive. Ultimately, Jarpa’s work rejects the idea that the archive is solely a device of extraction. Rather, her work emphasises that the archive constitutes a matter that requires a medium not only to be legible, but above all to stand out that which is illegible. That which can no longer be read, that which history can never tell, but which paradoxically is inscribed in it. Which is forcefully present, absolutely visible. The archive is, clearly, a weighty problem.

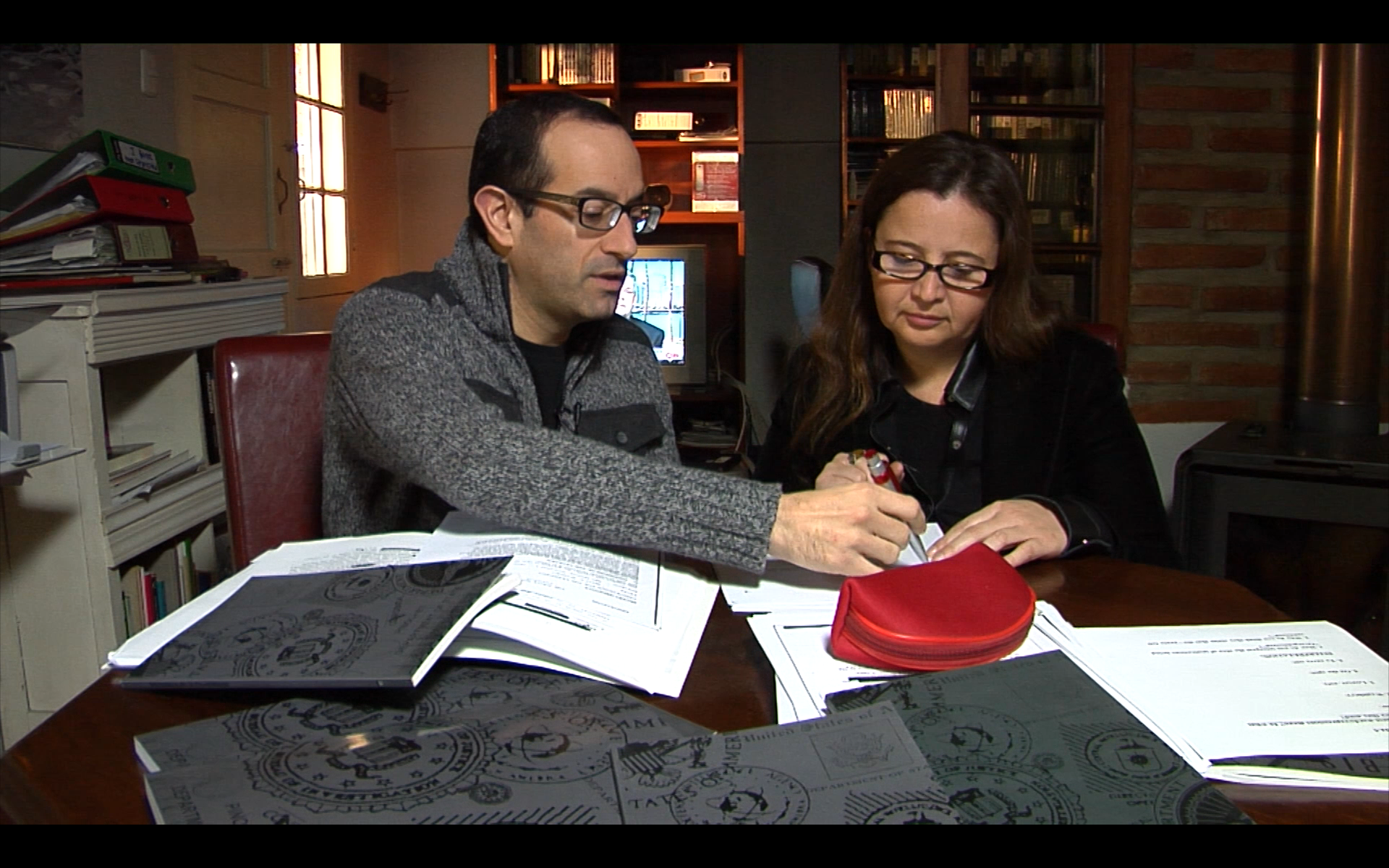

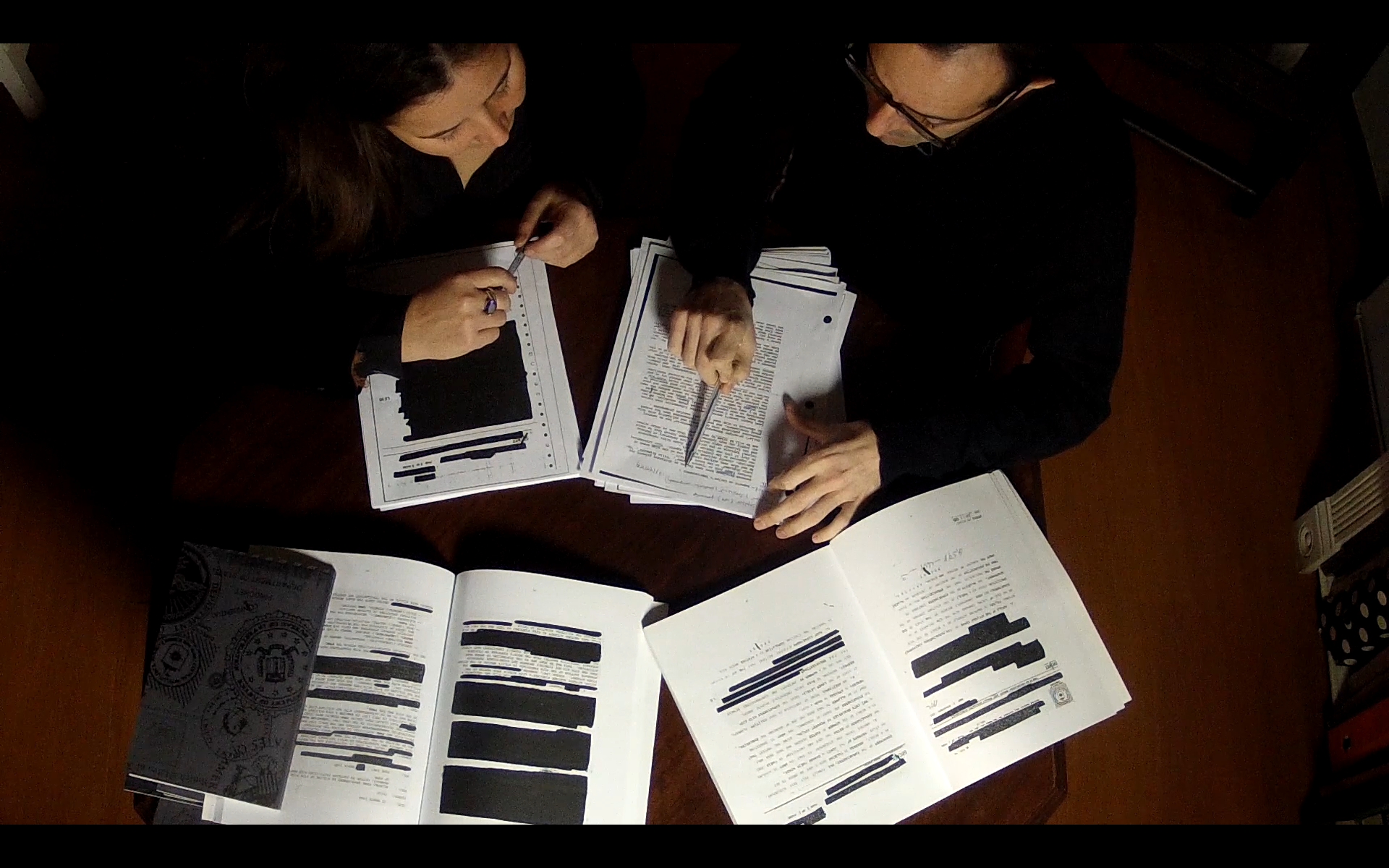

Drawn by the massive declassification that took place in the United States during Bill Clinton’s administration, Jarpa was struck by its material condition. That is to say, the artist became concerned about the overwhelming presence of crossed out sections. Blacked out to veil those compromising contents that remain hidden despite their declassification. That which may never come to light, that which remains classified. Jarpa states: “I suffered a second shock because many of these documents were blacked out –– entire paragraphs and pages erased with black lines and blocks. I was moved by this erased information and, in turn, by the history of Chile, which I felt, through that erasure, as small and insignificant” 1 . The artist begins her enquiry by evidencing the irreversible process of archival expurgation. However, despite the fact that her work begins and is even sustained by the violence of what has been crossed out, of what has been banned, of what has not been shown and, therefore, of what has been cut out of history; what she really emphasises is that this same crossed-out material, to which we may never have access, is capable of recovering its decidability despite being marked with the sign of the unspeakable; its legibility despite being stigmatised with the sign of the illegible; its affirmative condition despite being cut off with the sign of the crossed-out. It is as if that which censures justice and truth were turned against the perpetrators and were the only evidence, not only of censorship itself ––of the violence to which bodies and documents have been subjected–– but of the opacity with which, paradoxically, the past can be better read and, I would say, better written. The artist reveals the most complex dimensions and the scope of the obscure gaps in history2 .

For Voluspa Jarpa’s work exercises a blacking out pedagogy. Those crossed-out sections that ––by standing out from the revealed text, by becoming a clear image–– manage to expose the connections and practices that are inscribed in the document, no longer as a mere obstacle or contingency, but as a fundamental part of the history it encompasses. By becoming legible images, these opaque geometries discontinue the external condition of what is crossed out, that is to say, they become intrinsic to every document and, of course, to every archive.

Rather, I propose that Jarpa’s work suggests that these blacked out sections go far beyond secrecy, surveillance and the restriction of access to compromising information: they are able to account for how the state of exception is structured, how the fabric of history is told, how permission to narrate is exercised, as Edward Said 3 conceived it, and furthermore, how the archive is made up, not just the one dressed in black, but all archives. The blacked out sections, then, record necessary clues to programme the assemblage that the archive requires, to come closer to producing the proscribed narrative of our difficult history.

And this account of the opacity of this archive leads the artist to discuss the art field of the 1960s and 1970s, which was dominated by American Minimalism. Minimalism and the intervention of the United States in Chile seem to be associated, then, to what I call here the politics of form. We may consider that this work threads geometric abstractionism and monochrome with the atrocious document, which in principle share temporality, appear simultaneously. Jarpa’s work activates the political relations that pass through the form between the work of artists such as Frank Stella or Donald Judd and declassified documents. Formal coincidences between minimalist art and the declassified document suggest a continuity between aesthetics and politics, and emphasise an association that can only be detected when understood as a politics of form. That is, form reveals the epochal complicity between aesthetics and US imperial policies of the 1960s and 1970s.

Likewise, such correspondence also reveals the ability of Jarpa’s work to find in the blacked out sections of the declassified ––in the transformation that the censorial contingency finally makes possible, that is, in the way in which information becomes image–– a matter that is legible beyond its pure condition of erasure, its formulation as an accident of history. Because the Chilean artist refuses to invite us to decipher that which lies beneath what has been blacked out, or even to speculate on what might lie there, but rather to situate a new opaque alphabet whose opacity allows us to read that which the documents unlawfully hold but also what they exceed. The blacked out sections are even more eloquent, they are capable of revealing much more than the naked document itself.

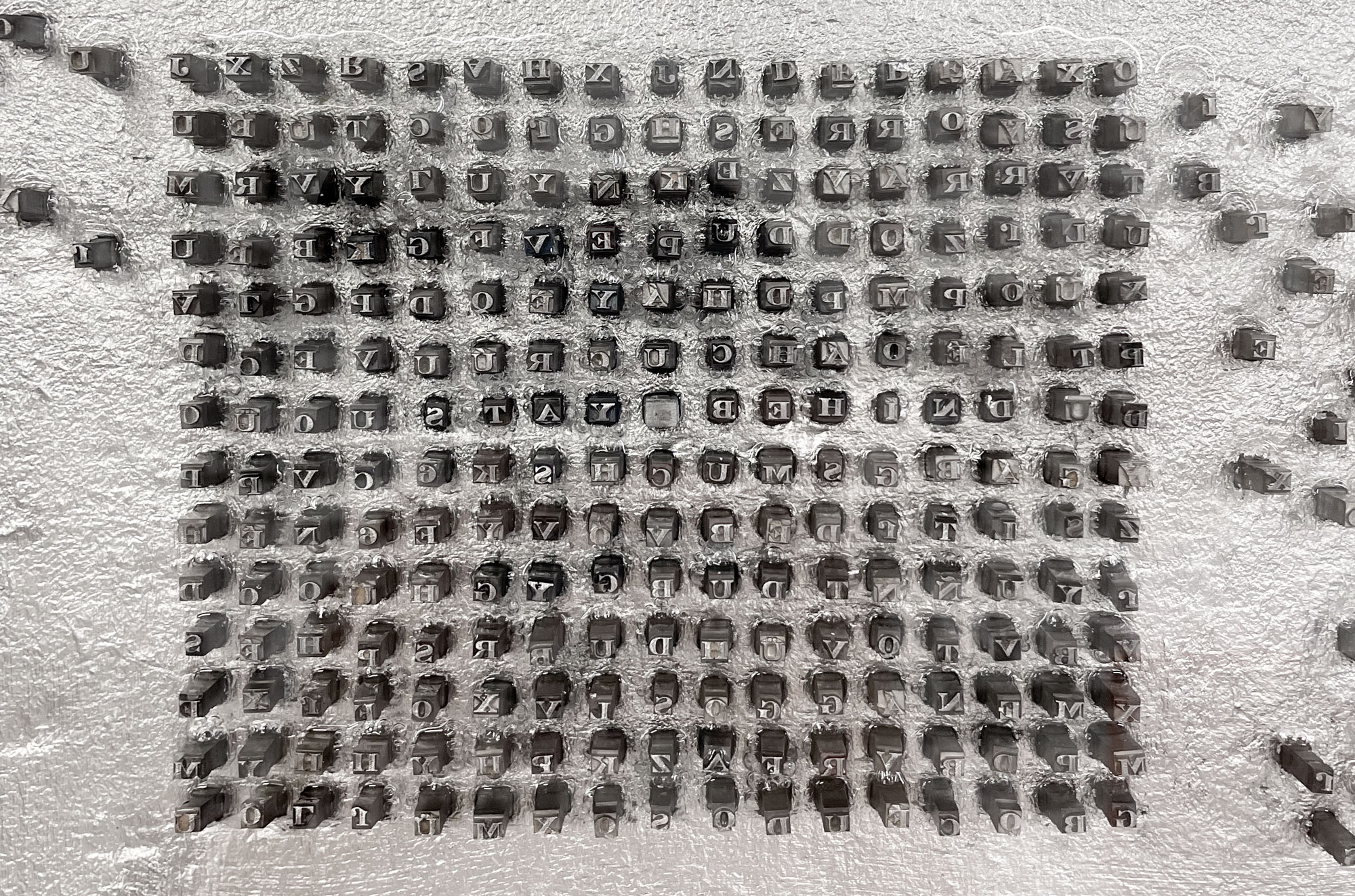

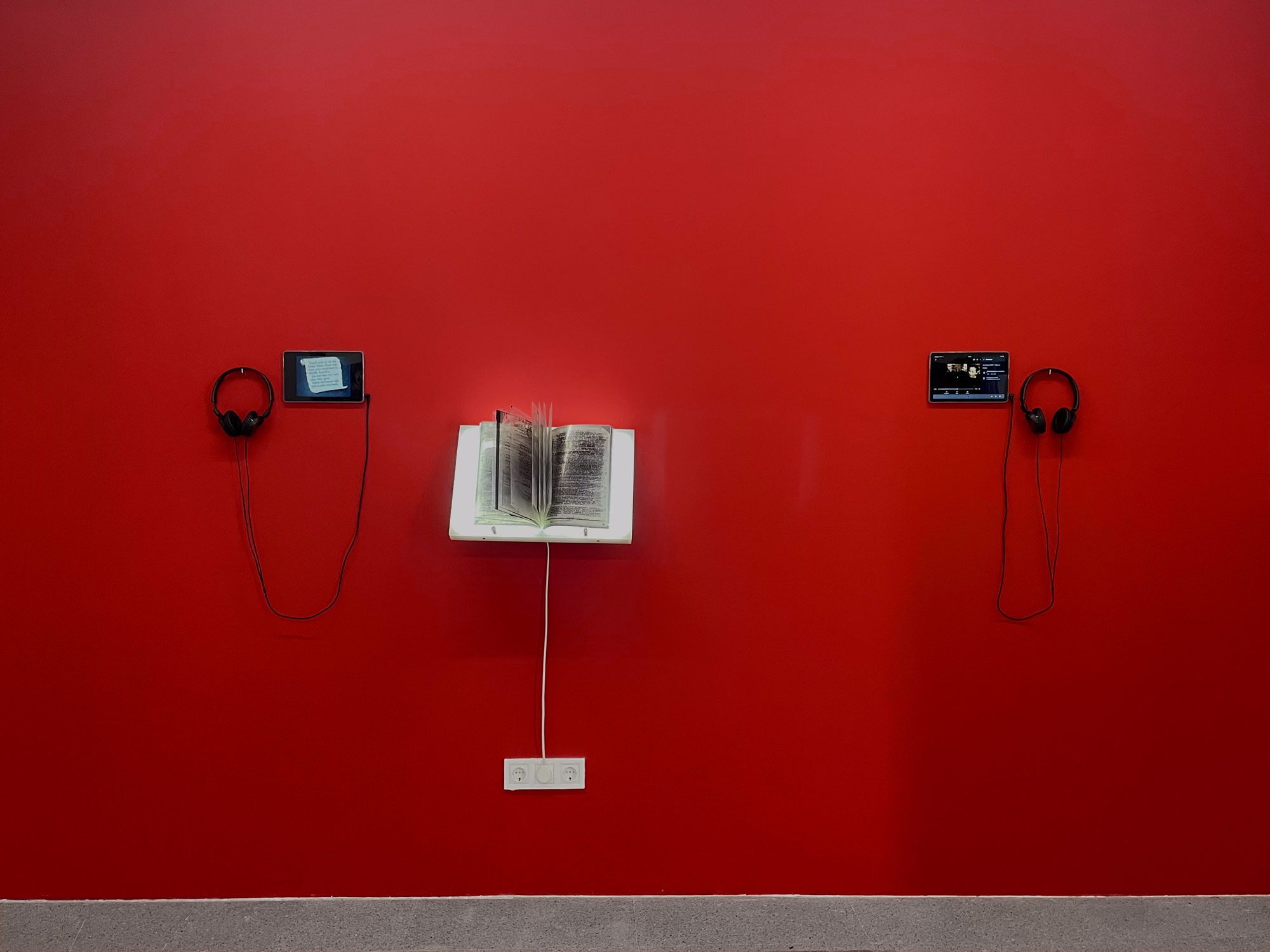

And to account for the fact that these blacked out sections, which reveal as well as conceal, that they are confronted with the productive relations that made their condition of matter possible: I am referring to the production devices of these same documents. With her assemblages, Voluspa Jarpa proposes to penetrate the matters responsible for her writing. When she tackles the declassified documents of the Cold War, the artist reaches into the deepest corners of the typewriters that possibly produced the now declassified documents in order to try to read ––on their time-worn keys, on their crumpled types and rollers–– that which they printed at a distant time, that which is still embedded and jammed in the devices for producing documents. For example, in the piece Artilugio Historia (Device History) the artist intercepts three materials: declassified documents, burnt books and a metal stamp with steel types from an analogue printing press that does not compose intelligible words. This assemblage that transforms the destructive and obstructive function of history ––the censorship of documents, the burning of books typical of totalitarian reason and the intervention and closure of printing presses–– becomes a device for the production of meaning that manages to evade that which obstructs it and then presents itself as a novel war machine 4 .

Voluspa Jarpa’s impressive work makes it possible to expose the ways in which obstruction, destruction and censorship become productive and constitute not only the repressive apparatus of the state but also the architecture that manages its memory. The blacked out sections of the declassified document become a foundational exercise in investigating the most radical political events: from the assassination plots against political leaders in Latin America or the surveillance of post-structuralist intellectuals during the Cold War, to the Chilean outbreak of 2019 and the ocular trauma of an entire country. Ultimately, Voluspa Jarpa makes the crossed-out document, which will later become the crossed-out eye of the Chilean protests, the legible principle of her highly complex politics of form.

Javier Guerrero

1. Voluspa Jarpa, “Historia, archivo e imagen: sobre la necesidad de simbolizar la historia”, A Contra Corriente, 12(1), 2014, 23.

2. Peter Kornbluh argues that documents are essential for the reconstruction of history but they can never reconstruct the whole story: there are certainly undocumented portions that need to be remedied. Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability (New York: The New Press, 2003, xviii).

3. Edward Said, “Permission to Narrate”, Journal of Palestine Studies, 13(3), 1984, 27-48.

4. Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari, “A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia”, University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

exhibición:

ciudad:

país:

Especificación:

- 2024

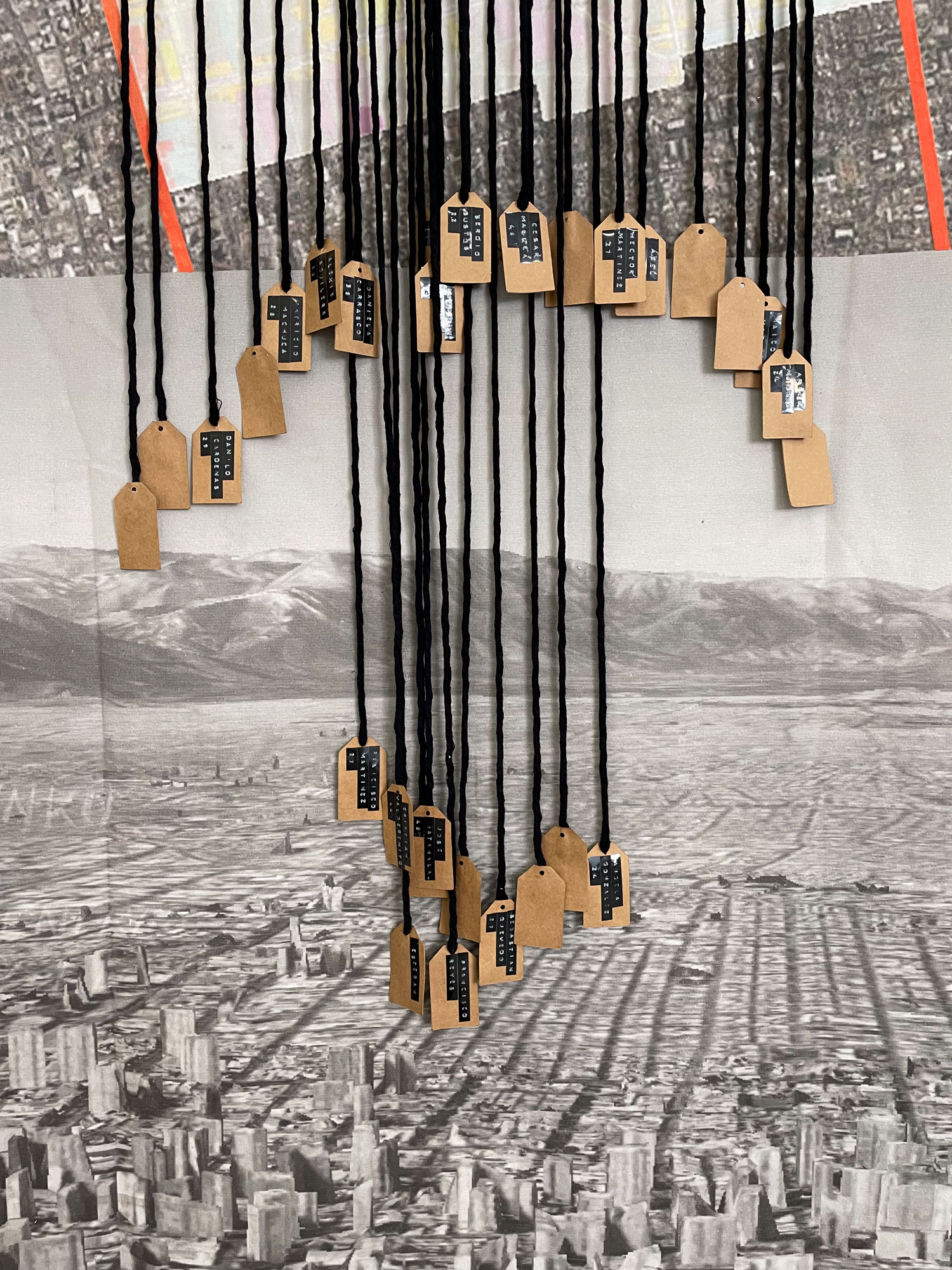

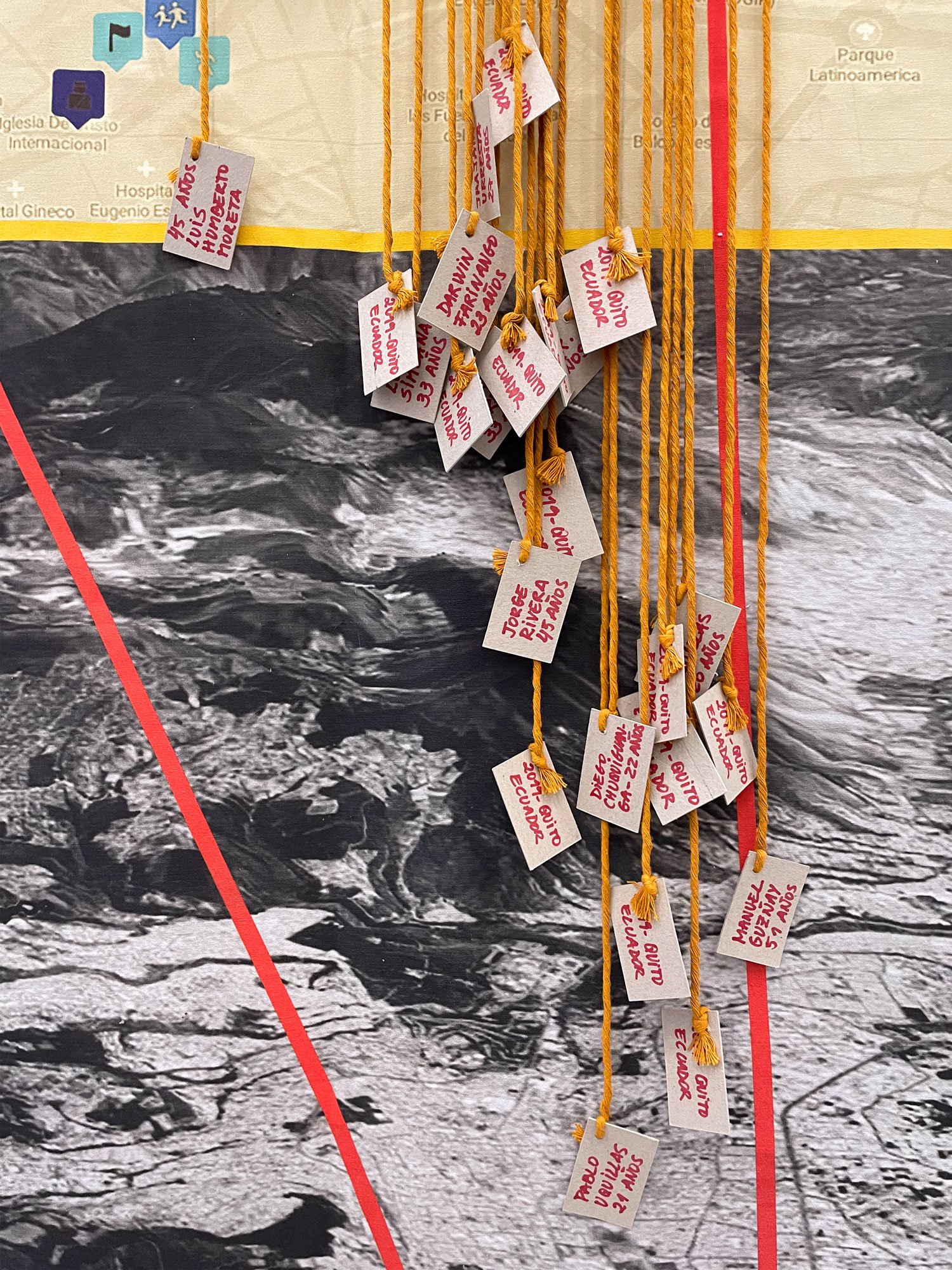

Cartografía Incógnita

(Incognito Cartography)

Intervened map - 2024

Cartografía Incógnita

(Incognito Cartography)

Intervened map - 2024

Andes

Intervened map - 2019-2023

Cartografías de la Sindemia

(Cartographies of the Syndemic)

7 digital prints on large format fabric with mixed media interventions - 2023

Sindemia

Video - 2016

Yo no soy un hombre, soy un pueblo

(I am not a man, I am the people)

Marker, graphite pencil, and digital print on polyester paper - 2016

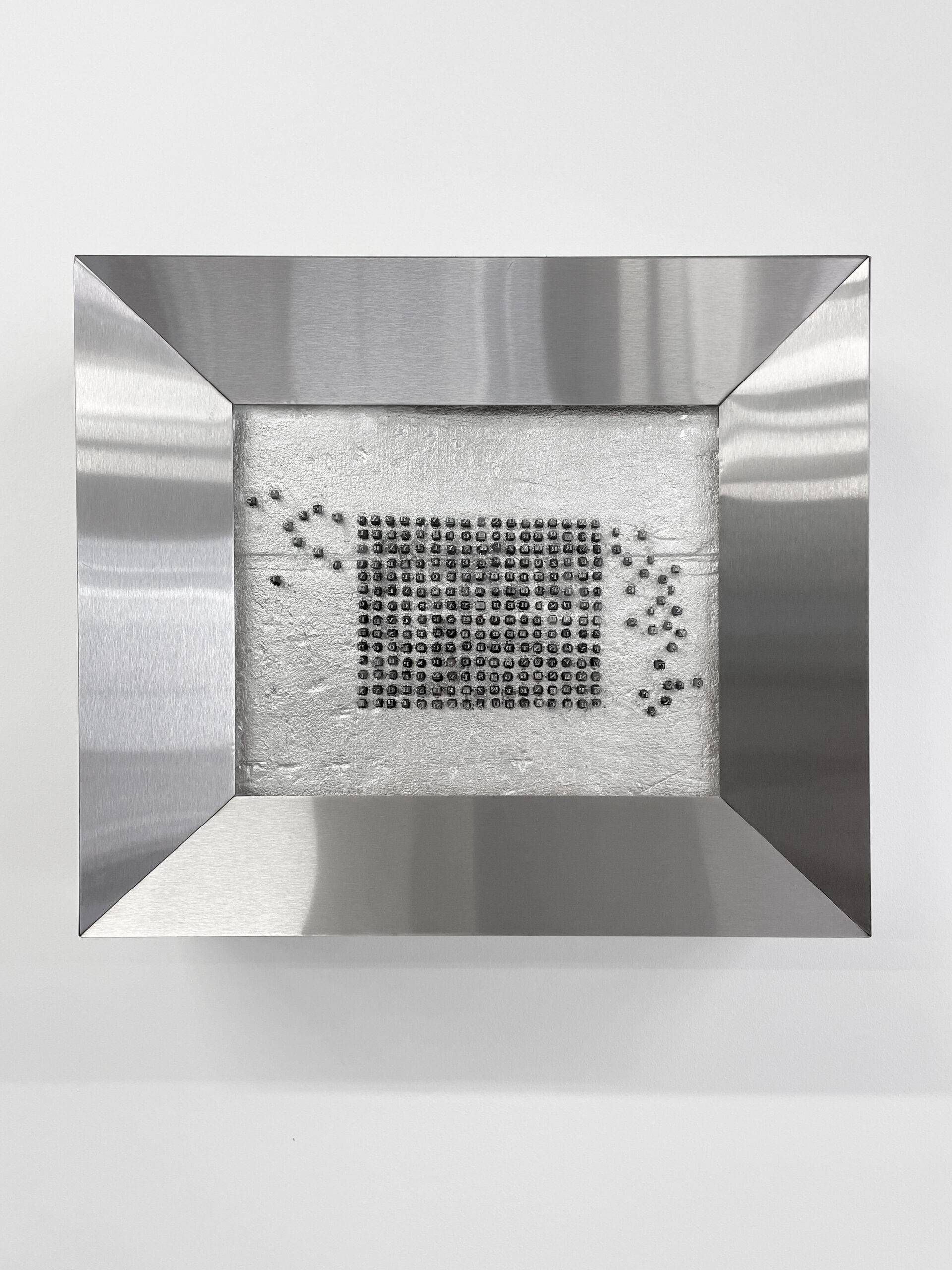

Serie Lo que ves es lo que es / Judd Cubos

(What you see is whai it is Series / Judd Cubes)

6 MDF cubes coated with stainless steel, engraved phrase, and 6 acrylic blocks containing 17 laser-cut documents - 2016

Todo se desvanece en la niebla

(Everything fades into the fog)

29 stainless steel folders with documents printed on paper - 2022

Gladio

Adhesive graphic on wall, 18 graphite drawings on paper and 16 bronze coats of arms with acrylic supports - 2017-2024

Stay Behind

Steel and glass box with typographic stamps - 2019

Libro de la República Bananera

(Banana Republic Book)

Lightbox with transparent PVC printings - 2019

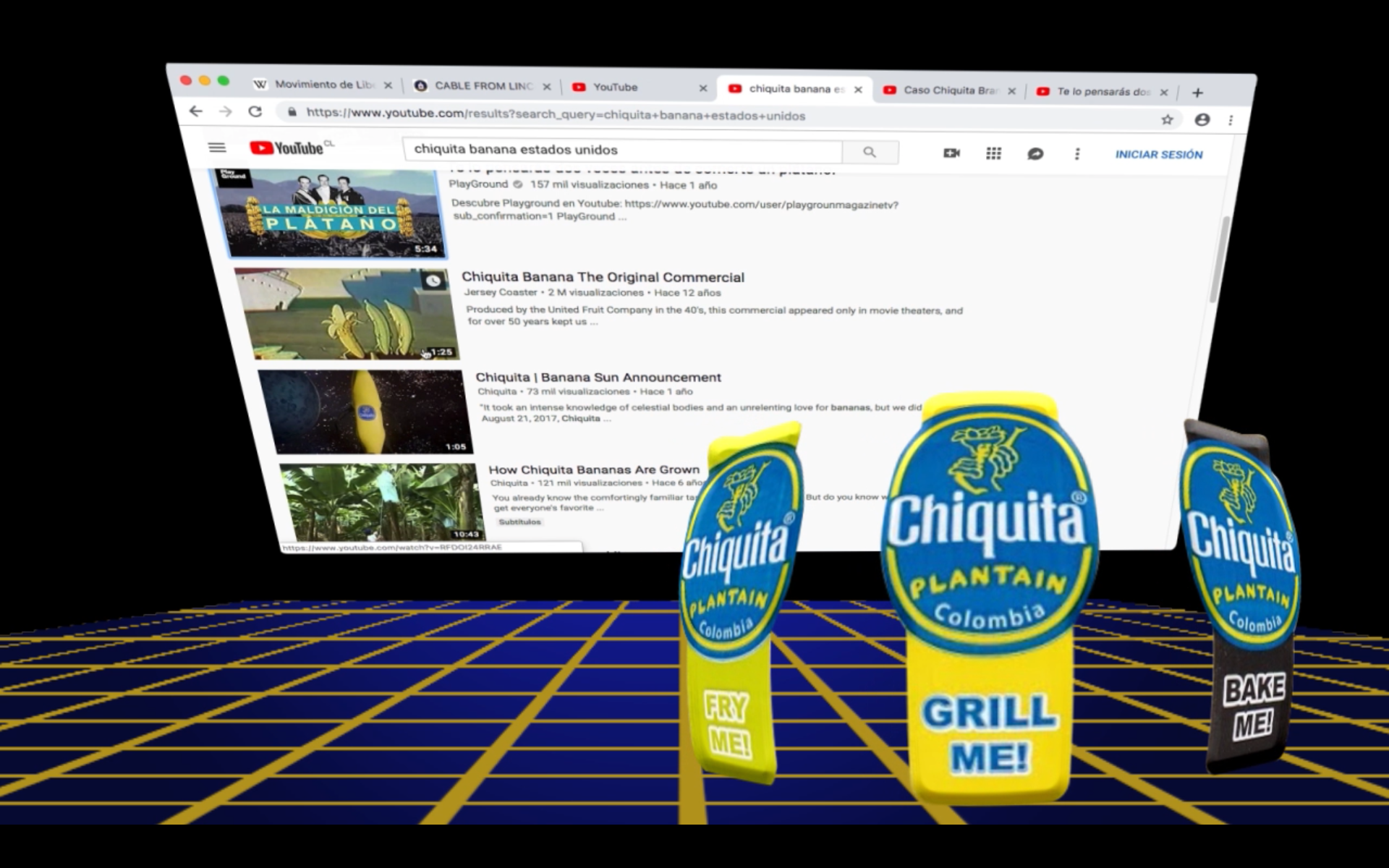

Chiquita Banana

Video - 2019

Journey to Banana Land

Video - 2016

Translation Lessons

Video - 2016

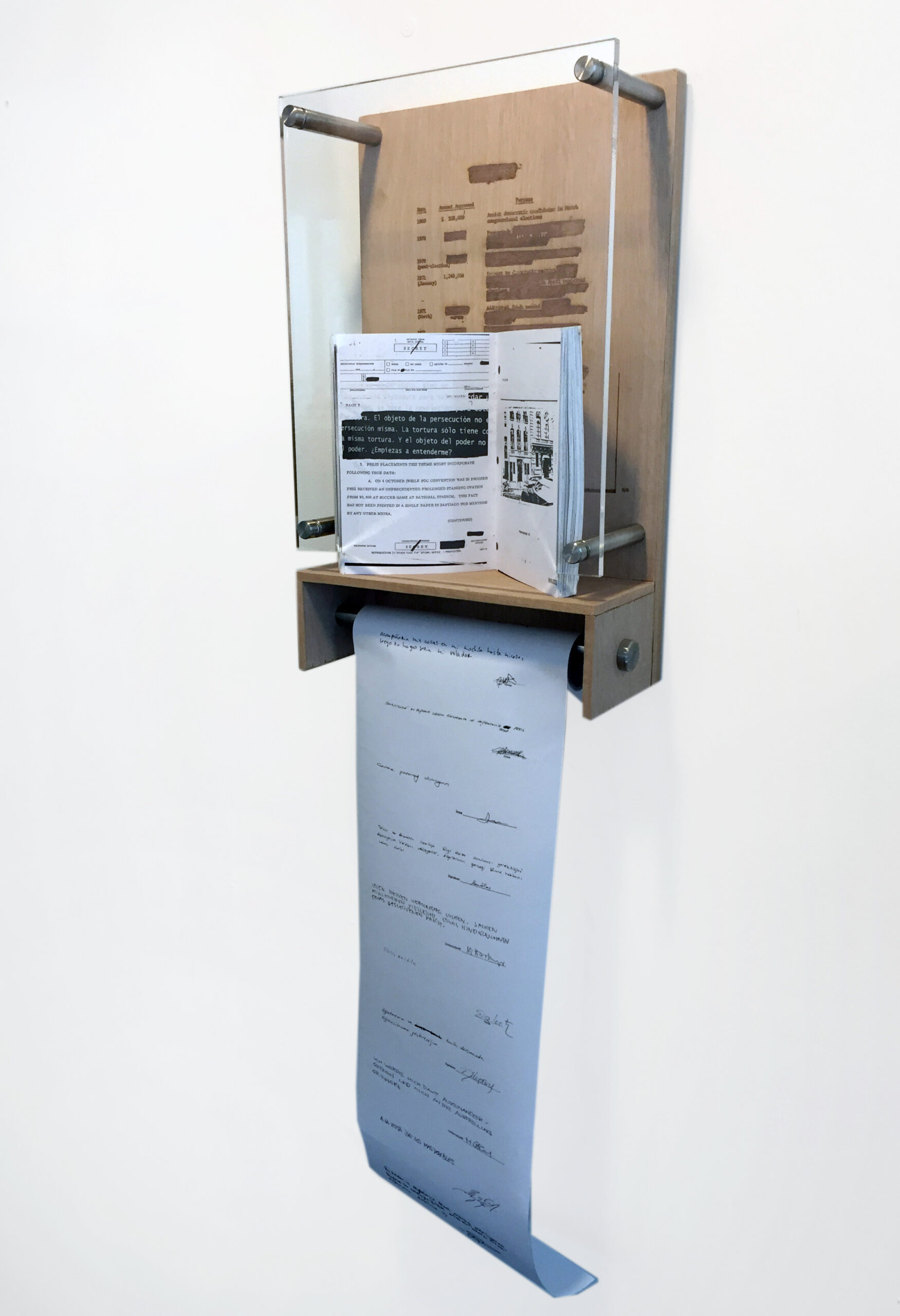

Respuestas para la Distopía

(Answers to Dystopia)

Laser engraved wood, separations and metal bar, laser engraved acrylic, book and print on backlight film

PHOTOS: La Oficina